Buy the photo Svalbard Reindeer by Kai Müller on canvas, ArtFrame, poster and wallpaper, printed on demand in high quality.

About "Svalbard Reindeer"

by Kai Müller

About the artwork

The Svalbard reindeer has experienced many ups and downs: migrating from the Russian Arctic thousands of years ago, it has evolved into its own subspecies (Rangifer tarandus platyrhynchus). In the 19th and early 20th centuries, it was hunted so heavily that the population was wiped out in many parts of its range. It is estimated that there were only perhaps 1,000 animals left when the species was placed under protection in 1925 - the same year that the Svalbard Treaty came into force, allowing the Norwegian government to take legal action. Svalbard reindeer can travel long distances, including over frozen fjords and even drift ice, otherwise they would never have reached Svalbard. But they don't necessarily do that, because their normal way of life is to stay where they are as long as the conditions are suitable. So it takes time: after local extinction, many decades can pass before reindeer find their way back to remote parts of the Svalbard archipelago. In addition, local populations are subject to strong short-term fluctuations: In bad years, for example when rain on the snow-covered ground in winter covers the tundra with a hard crust of ice, making the vegetation inaccessible, a considerable part of the population starves to death in spring. According to biologist Le Moullec, however, this usually only becomes a problem when the population is already so high that the remaining accessible areas can no longer feed the population: A classic case of self-regulation of a natural ecosystem. In addition, the risk of falling increases in icy terrain: in the winter of 2018-19, several reindeer died in the vicinity of Longyearbyen, for example in Bjørndalen, after falling from steep slopes.

About Kai Müller

For as long as I can remember I have always been drawn to the beauty of the environment and the wild spirit of wildlife. However, my love for nature and wildlife photography began a few years back after a series of travels coupled with my studies in design. .. Read more…

Germany

Germany Ordered in February 2025

Ordered in February 2025

Germany

Germany Ordered in August 2025

Ordered in August 2025

Germany

Germany Ordered in August 2019

Ordered in August 2019

Netherlands

Netherlands Ordered in October 2022

Ordered in October 2022

Netherlands

Netherlands Ordered in January 2024

Ordered in January 2024

Germany

Germany Ordered in November 2024

Ordered in November 2024

Germany

Germany Ordered in November 2021

Ordered in November 2021

Netherlands

Netherlands Ordered in August 2019

Ordered in August 2019

Netherlands

Netherlands Ordered in December 2024

Ordered in December 2024

Netherlands

Netherlands Ordered in July 2023

Ordered in July 2023

Germany

Germany Ordered in February 2023

Ordered in February 2023

Germany

Germany Ordered in March 2019

Ordered in March 2019

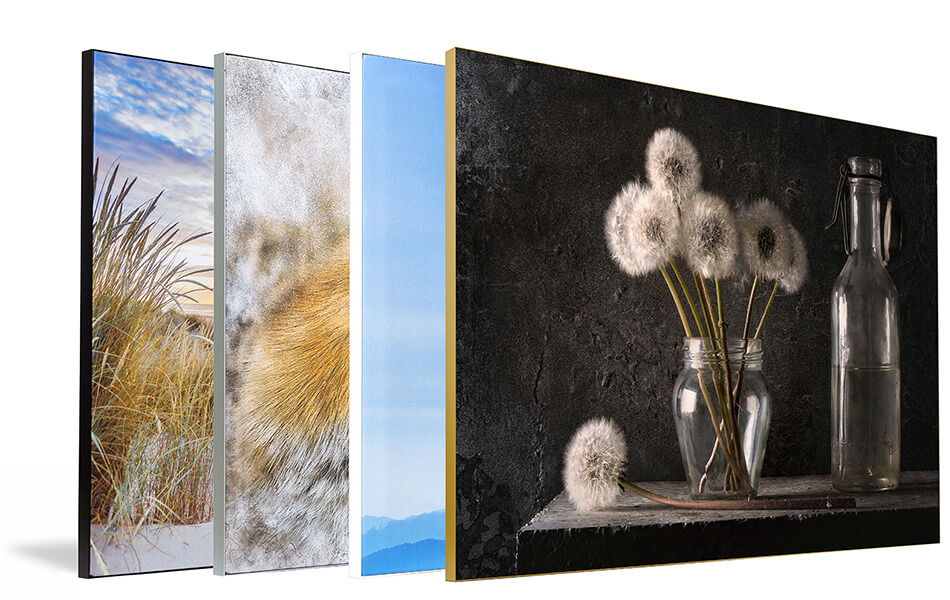

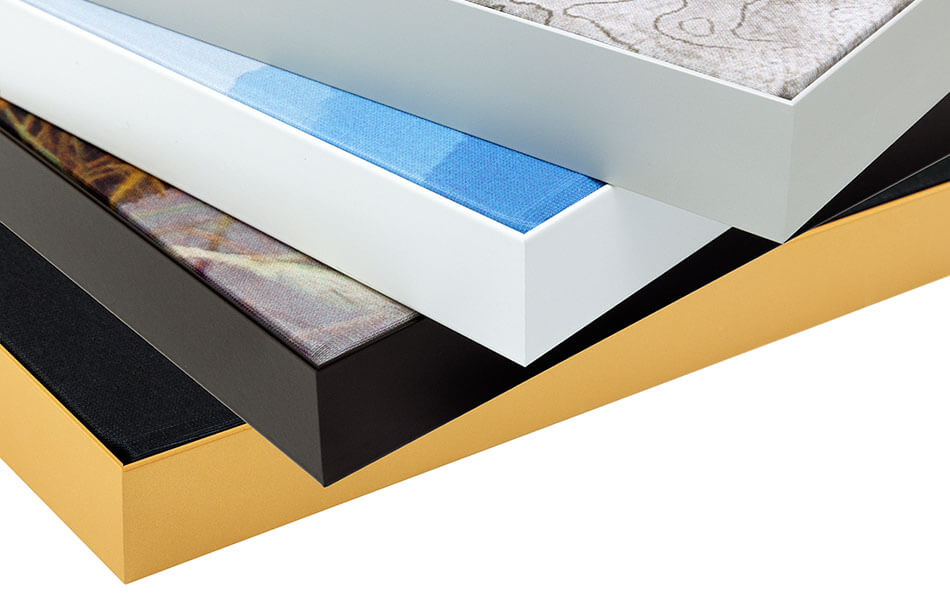

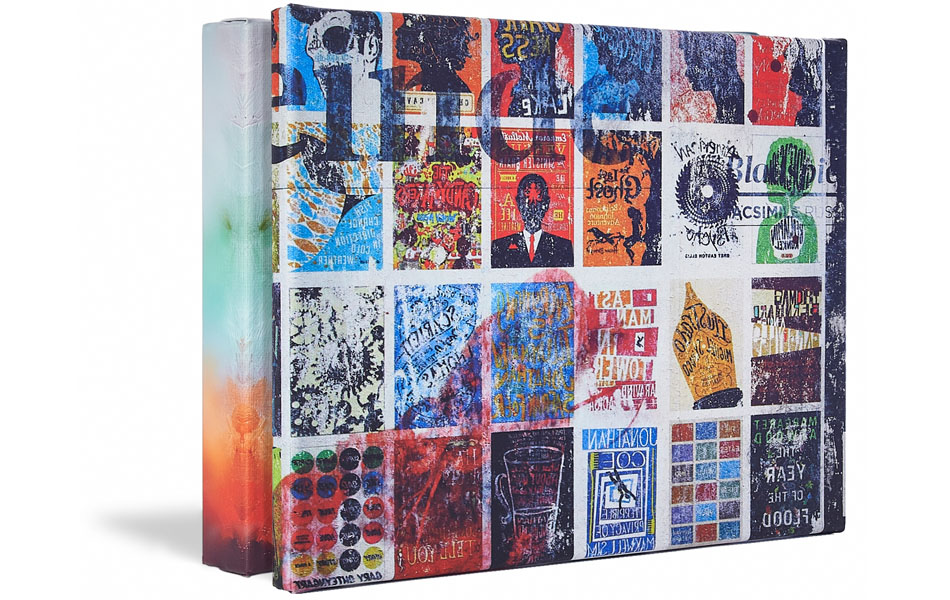

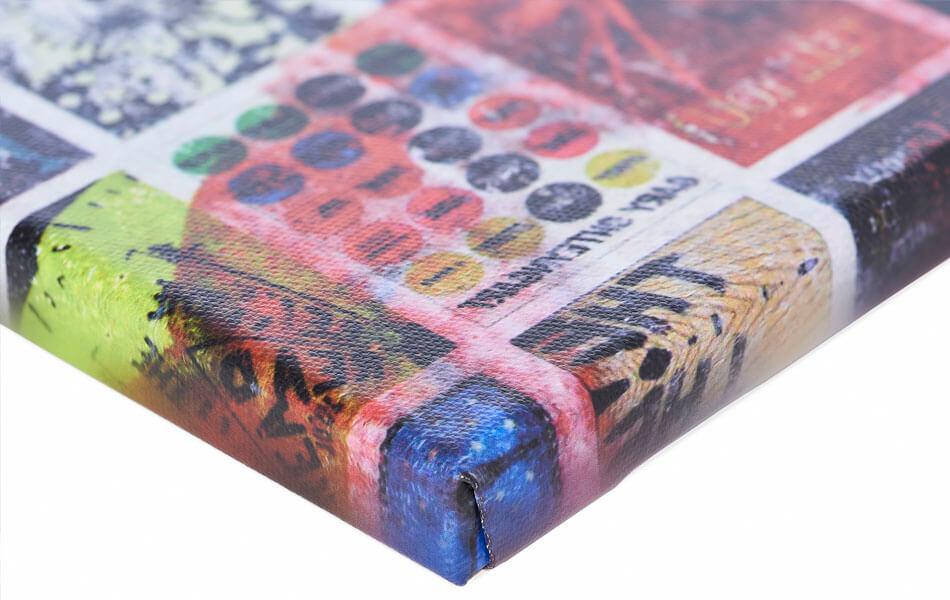

About the material

Wallpaper

Make a statement with art on wallpaper

- Razor-sharp prints

- Easy to apply

- Big sizes possible

- Strong quality

Discover the artworks of Kai Müller

Reindeer herd in Pasvik National ParkKai Müller

Reindeer herd in Pasvik National ParkKai Müller Northern Lights Panorama LofotenKai Müller

Northern Lights Panorama LofotenKai Müller Polar FoxKai Müller

Polar FoxKai Müller AgardhbuktaKai Müller

AgardhbuktaKai Müller Paulabreen SvalbardKai Müller

Paulabreen SvalbardKai Müller Longyearbyen photographed from the mountain SarkofagenKai Müller

Longyearbyen photographed from the mountain SarkofagenKai Müller Evening atmosphere in Pasvik National ParkKai Müller

Evening atmosphere in Pasvik National ParkKai Müller Hiorthamn SvalbardKai Müller

Hiorthamn SvalbardKai Müller Pack ice in the AsgardbuktaKai Müller

Pack ice in the AsgardbuktaKai Müller Reindeer herd in Pasvik National ParkKai Müller

Reindeer herd in Pasvik National ParkKai Müller Uttakleiv on the Lofoten under the northern lightsKai Müller

Uttakleiv on the Lofoten under the northern lightsKai Müller Aurora Borealis before the mountainsKai Müller

Aurora Borealis before the mountainsKai Müller WhalersKai Müller

WhalersKai Müller Reine LofotenKai Müller

Reine LofotenKai Müller Northern lights over the lighthouse of SlettnesKai Müller

Northern lights over the lighthouse of SlettnesKai Müller Sommarøy in the winter evening lightKai Müller

Sommarøy in the winter evening lightKai Müller Giant Iceberg Antarctic PeninsulaKai Müller

Giant Iceberg Antarctic PeninsulaKai Müller Drift ice in the AntarcticKai Müller

Drift ice in the AntarcticKai Müller HallingskeidKai Müller

HallingskeidKai Müller Lofoten ReineKai Müller

Lofoten ReineKai Müller

Christmas

Christmas Photo wallpaper

Photo wallpaper Photography

Photography Safari

Safari Serene Peace

Serene Peace Spitsbergen

Spitsbergen